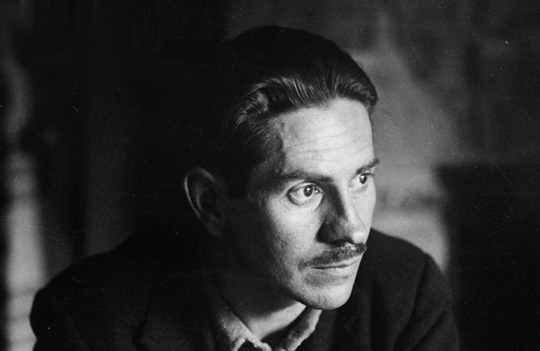

A bronze bust rests on a pedestal at the corner of Drake and Wave Streets next to the Monterey Bay Recreational Trail. It depicts a pleasant, studious looking man. A magnifying loupe hangs around his neck, a pen is clipped to his opencollared shirt; he holds a sea star in his hand. More often than not, the star is joined by a sprig of flowers some passerby has placed there. This is Edward Flanders Robb Ricketts, known to his legion of friends—both famous and infamous—as Ed. Not “Doc.”

Many—if not most—Monterey Peninsulans will confidently aver, however, that that statue is a likeness of “Doc Ricketts.” Perhaps it’s an understandable misconception. After all, Ricketts’ pal John Steinbeck modeled one of his most beloved characters on him. “Doc” was the hero of Steinbeck’s novels “Cannery Row” and “Sweet Thursday.”

“Nowhere did Steinbeck string the two words ‘Doc’ and ‘Ricketts’ together,” says Cannery Row historian and author Michael Hemp. Steinbeck did, however, borrow liberally from his good friend’s personality to form the character of Doc (and others, including ex-preacher Jim Casy in “The Grapes of Wrath”). Others have perpetuated the name, however. A popular nightclub named Doc Ricketts’ Lab operated for many years in a former cannery building, and the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute operates a remotely operated underwater research vehicle named Doc Ricketts. Even Time magazine got in the act, publishing a 2003 story, “The Ghost of Old Doc Ricketts.”

The real Ricketts operated Pacific Biological Laboratories at 740 Ocean View Avenue (now 800 Cannery Row). He was in the business of providing preserved specimens for study by schools and universities. By all accounts, Ricketts was generous, personable, and well-loved—as was Steinbeck’s Doc. There are few alive today who knew the man. One is Frank Wright of Carmel, who met Ricketts while they both served in the Army during World War II at the Presidio of Monterey. “He was a hell of a guy,” Wright recalls.

“Cannery Row” was published in 1945, three years before Ricketts’ death, and was a stellar success, making the scientist an instant celebrity. “People were knocking on his door all the time,” Wright recalls. “It drove him crazy: ‘Are you Doc?’ ‘No. I’m Ed Ricketts.’”

He was very polite, however. “When people came, he talked to them,” Wright adds. “If they were interesting enough, he asked them in.”

The much younger Wright spent many hours with Ricketts at the chips and swigging Bergermeister beer purchased at the Wing Chong Market across the street. “Ed and I bonded through our mutual love of zoology,” he says. Indeed, following his service, Wright was inspired by Ricketts to return to UC Berkley to earn a degree in biology.

Ed Ricketts was egalitarian by nature. In addition to befriending young Army draftees, his circle of friends was varied: he was close to at least two of America’s leading writers, John Steinbeck and Henry Miller, plus noted mythologist Joseph Campbell and a host of lesser-known artists and intellectuals.

But Ricketts was just as comfortable hanging out with the human castoffs that inhabited the gritty, smelly area that the now-pristine tourist mecca Cannery Row was in those days.

“There’s an incredible magnetism to Ed Ricketts,” says Eric Enno Tamm, author of “Beyond the Outer Shores: The Untold Story of Ed Ricketts.” “That’s evident in the type of people who were attracted to him. Industrial Cannery Row was an unusual place to find artists and philosophers. The fact that people clustered around the lab speaks volumes about the kind of person Ed was.” Ricketts’ friendship with Steinbeck is perhaps the most celebrated. Stories on how they met vary, but indisputably, the two became close chums. Steinbeck spent many happy hours at the lab, helping preserve specimens, learning about marine biology and just hanging out. Indeed, in 1936, when the lab building and everything in it burned to the shoreline, the famous author became a 50-percent partner in the business after funding its reconstruction.

Ricketts’ interest in the sea and its critters went way beyond their commercial value. Although he studied zoology at the University of Chicago, his native city, he didn’t earn a degree. His natural curiosity and talent led him to publish “Between Pacific Tides,” a scholarly and pioneering book that examined the ecosystems that interact to make up the marine environment. The work is still in print and is highly regarded. “If you are a marine biologist,” says Steve Webster, co-founder and retired Senior Marine Biologist with the Monterey Bay Aquarium, “you own a copy of ‘Between Pacific Tides.’”

In 1940, Ricketts and Steinbeck hatched a plan to journey to the Sea of Cortez to study that habitat and collect specimens. Chartering the Monterey fishing vessel Western Flyer and her crew, they launched on a sixweek adventure that was chronicled in “Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research.” The first section of the book is a salty narrative of the journey penned by Steinbeck, while the second is a more scholarly account by Ricketts, detailing the discoveries they made. Following Ricketts’ death, Steinbeck’s section was reprinted as “The Log from the Sea of Cortez,” omitting the biologist’s contributions. The author did, however, add “About Ed Ricketts,” a heartfelt biography and tribute to his friend and collaborator.

Frank Wright was one of a group of men who purchased the lab building in the 1950s for use as a private clubhouse. The facility had become rundown and unlivable after Ricketts’ passing. The group paid the princely sum of $14,000 for the property. “We once had an offer of $1 million from the Monterey Bay Aquarium,” Wright recalls. But one member, renowned cartoonist Eldon Dedini, put the kibosh on that potential sale. “He said, ‘They’ll probably fill it up with water and put fish in it.’ That was the end of that.” The building was eventually sold to the City of Monterey and has undergone an extensive seismic retrofit and upgrade. Great care was taken to preserve the character of the interior, however, and many details exist from Ricketts’ time there. Pacific Biological Laboratories was never a big moneymaker. Ricketts was always on the edge financially, but it seems as though monetary comfort wasn’t all that important to him. He was happily satisfied slogging around tidepools looking for new species, or sitting by the cranky furnace at the lab, talking philosophy with a group of friends. But his contribution to marine biology is unquestioned.

Ricketts’ work became one of the touchstones of the scientific community; his thinking—especially his view of how various ecosystems intermesh and work together in an environment—was decades ahead of its time.

“I really felt that history hasn’t given Ricketts his due,” Tamm says. “But the fictional character really came to overshadow this great thinker and great scientist. A man who dedicated his life to collecting facts about the natural world has become, himself, a fiction.”

Ed Ricketts’ bronze likeness is sited on the very spot where on May 8, 1948, he was mortally injured when a train collided with his Buick sedan. A genuinely nice guy to the end, when pulled from his mutilated automobile by a police officer, his first words were, “Don’t blame the motorman.” That’s just the kind of guy Ed–and come to think of it, “Doc”–was as well. The Pacific Biological Laboratories building is open occasionally for public tours. Michael Hemp and Frank Wright are in attendance, ready to regale visitors with the truth about Ed Ricketts, “Doc,” and the difference between the two.

Visit www.canneryrow.org for schedule.