Gritty, stinky yet prosperous industrial district. Mythologized parable of post-World-War-II California life. Abandoned, rusty, dangerous no man’s land. World-famous tourist attraction with a curious mix of old and new, kitschy and classy, high tech and old school.

That’s Cannery Row: a miasma of contrasts; a place with a dramatic past peopled with a cast of unique, often-oddball, always interesting characters and an unlikely trajectory of boom and bust and boom.A phoenix, risen from the ashes of neglect and economic hard times to become a majorWest Coast attraction drawing between three and four million visitors annually.

As historian Michael Hemp writes in “Cannery Row: the History of John Steinbeck’s Old Ocean View Avenue,” this chock-a-block mix of tchotchke shops, fine dining establishments, scientific institutions, T-shirt stores, highend jewelry shops and pampering hotels is “a street with every right to be dead.” But it’s not. In fact, it’s thriving, thank you very much.

And it’s all due to a silvery fish, the California sardine, sardinops caerulea. These animals were once so plentiful in the Monterey Bay that it spawned a multi-million dollar industry dedicated to turning their protein-rich bodies into food and fertilizer for the world. In halcyon years, more than a quarter-million tons of sardines were processed in highly efficient, state-of-the-art factories.

But they went away. No one knows why, only that they did. The factories went to sleep; rust, rot and ruin took over the once bustling Ocean View Avenue.Then a local guy, John Steinbeck, a writer possessed of great talent and a keen eye for the nuances of human interaction, penned the novel “Cannery Row.” Published in 1945, it immediately put the place on the map.

Monterey city fathers of the 1950s renamed the street in homage to Steinbeck’s runaway best seller. But the sardine population paid no attention to the fancy new name and the buildings along Cannery Row began their slow deterioration into seediness.There were a few hardy individuals here and there, and entrepreneurs—including Neil DeVaughn, Kalisa Moore and Dick O’Kane—saw the Row’s potential and opened eating and drinking establishments amid the decaying factories.

In 1968, a pair of dapper gentlemen with some restaurant experience, a lot of ideas and plenty of chutzpah opened an eatery in a building that formerly housed a cafeteria for cannery workers. Young Ted Balestreri and Bert Cutino were operating on a shoestring. But their presentation of then-emerging fine California cuisine coupled with white-glove service and a stellar wine selection was and remains a big hit. In the beginning, the contrast of Sardine Factory diners parking in a decaying industrial neighborhood and entering to an elegant setting to be tended by waiters in tuxedos was a pleasant surprise. “It was kind of like going into a speakeasy,” jokes Balestreri.

Much has changed on the Row, but a surprising number of artifacts and buildings remain from the canneries’ heyday.

Most notable is the tiny building abutting the famous and popular Monterey Bay Aquarium. The home of the Pacific Biological Laboratories, this humble structure was the workspace of Ed Ricketts, immortalized in Steinbeck’s works as “Doc” Ricketts, the protagonist of “Cannery Row.” Visitors routinely walk past this building, not knowing it is a vestige of the days when the Row was, in Steinbeck’s words, “a poem, a stink, a grating noise, a quality of light, a tone, a habit, a nostalgia, a dream.” For years, it was a private clubhouse for a group of local movers and shakers and is now owned by the City of Monterey.

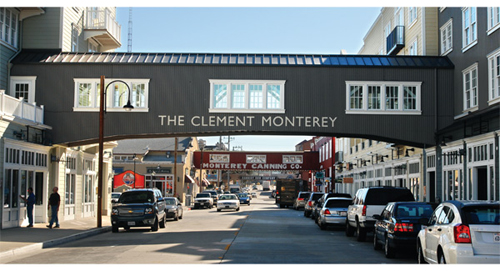

There are other structures remaining, most unchanged, at least outwardly: The Monterey Canning Company building, Wing Chong Market, Bear Flag, American Tin Cannery, and Enterprise Cannery buildings still exist, but now house shops, restaurants and office space. Scuba divers know that the underwater Cannery Row is a fascinating network of pipes leading offshore from the cannery buildings, once used to pump in the sardines offloaded by the fishing fleet.

Scattered here and there, both below the surface and above, are unidentifiable chunks of buildings and rusting pieces of arcane steel machinery. Massive tanks used to store sardine oil—one of the products made from the silvery fish—still loom above the Monterey Bay Recreational Trail, itself built on the right-of-way of the Union Pacific Railroad. It’s said that the tracks are still in place under the concrete trail, awaiting the day when a railroad returns to the Peninsula.

A few recent additions have generated quite a bit of buzz among a key demographic group that has not been a traditional habitué of the Row: locals.A state-of-the-art IMAX 3D theatre has been ingeniously shoehorned into the building that housed the Edgewater Packing Company and screens films in stunning high-definition and earth-shaking sound. Inter-continental the Clement Monterey Hotel brings luxury accommodations, world-class dining and impeccable service to a portion of the street that for many years looked like a forgotten construction project. And lovers of fine wines have an opportunity to sample the vintages of Scheid Vineyards in their sleekly elegant Wine Lounge.

Perhaps the most enduring remnant of old Cannery Row is the character that led a hardy generation to create the canning industry in the first place.That entrepreneurial spirit thrives, led by Balestreri and Cutino’s Cannery Row Company. Ever the optimist, Balestreri, President and CEO, believes, “The future is that Cannery Row is going to be the Riviera of Central California.”And he says it’s going to be hospitality that makes it so. “If we made you feel at

home when you’re here, we’ve made a mistake. Because our job is to make you feel better than you do at home.”

A Life Built on Hard Work and Sardines

Catherine Cardinale is a living reminder of Cannery Row’s heyday. She is the daughter of the first woman to be named a cannery supervisor and a former cannery worker herself. Husband Joe was Monterey’s youngest boat owner and skipper at the age of 22.

An active 80-year-old who seems half her age, Cardinale’s memories of working on the Row aren’t viewed through rose colored lenses.

“It was hard work. When the boats came in before dawn—sardine fishing was done at night—the cannery whistles would blow, calling us to work,” she recalls. “We had to stay until the entire catch was processed, sometimes 12 hours or more. It was cold, dirty work.”Not that she’s complaining— Cardinale’s generation didn’t feel sorry for themselves, they just went to work.

Although the Monterey Bay fishery was pioneered by Chinese and Japanese immigrants, the majority of the sardine fleet was manned by Sicilians. Many were from Isola delle Femmine, a flyspeck on the coast west of Palermo.

Fishing was—and is—a life of sacrifice, full of long periods away from home and family.However, Cardinale says that fishing ceased around the full moon and that gave the men five days to spend ashore. “Those were special times for us,” she recalls.“Both fishermen and cannery workers could rest, be together and have fun.” She remembers a strong spirit of community and picnics of sea urchins and mussels straight from the sea, on the sands of Pacific Grove and Pebble Beach.

Life was like that then on the Monterey Peninsula, when it was still very much a backwater and tourism hadn’t yet become an industry. The sense of community spawned by a relatively isolated immigrant population created ties still woven into the life and culture of this little corner of paradise.