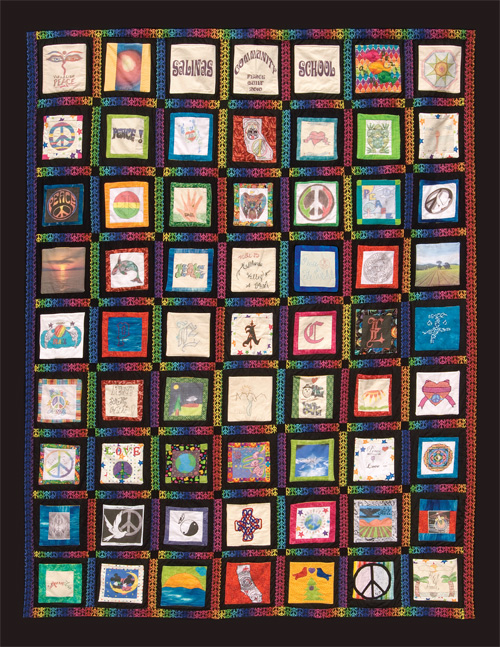

On an overcast morning at the Salinas Community School, a group of high schoolers dressed in shades of black and gray are working on their running stitch. Colorful sunsets, peace signs, doves, eagles and hearts are among the many designs being embroidered, drawn, and ironheat transferred onto fabric squares. The completed squares, or blocks, are stacked neatly on teacher Chris Devers’ desk, next to his approaching mathematics lesson. In a few weeks, the blocks will be joined together to form a “peace quilt.” It’s a project that has taken many hands to complete.

Laura Tinajero, an inter vent ion specialist at Second Chance, a Salinas nonprofit that does gang intervention and counseling, is helping finish a square that a girl now in juvenile hall didn’t get to finish.

“She is pretty proud of the work she accomplished,” Tinajero says. “With the quilting program they stay busy and it’s a new experience for them. Anytime you try something new, it opens doors.”

Devers, who speaks fluent Spanish, makes sure the class is staying focused while local volunteer Terry Uchida helps kids who have finished their block move on to other projects. Some boys are using a loom to knit black beanies, other kids are learning paper crafting, and one ambitious girl is sewing a purse.

Those who know what most of the students have already dealt with in their short lives realize just how meaningful a peace quilt is.

Salinas Community School is an alternative school with 60 students, run through the Monterey County Office of Education, and most of the kids at the school have been expelled from their previous schools.

It is the last stop before being turned over to the juvenile justice system, which is located next door. In five years of Devers teaching here, he says, 11 students have either been murdered or committed murder. It is a reality that is dealt with in the classroom while the focus remains on creating a better life.

“Everything that happens in Salinas flows through my kids,” Devers says. “The peace quilt gets kids to focus on habits of mind, settle down, show up on time, learn about starting and finishing a project, concentrating, and [paying attention to] detail. There is [the gain of] self-satisfaction, self esteem, problem solving—so much that goes into it. It is group work and integration of people into a common project.”

With hard work and creative programs that get the kids into nature, give them vocational training, and learn conflict resolution through a class developed with local nonprofit Global Majority, Devers says the school has seen huge successes in passing and attendance rates. This despite a very limited budget.

“We have the most contact [of anyone] with these kids,” Devers says. “We are where they feel safe. We are doing the most with the very least.”

For the students, one of the main frustrations seems to be a perceived lack of respect from the community at large for the efforts they are making at school. One girl who drew palm trees and an ocean against a vibrant sunset for her block says, “It shows peace against gang violence. It shows people who have a bad reputation can do good things. It’s fun, kind of hard.”

Last year, a peace summit at the school was capped off with a peace treaty. Devers’ friend, Terry Uchida, a local craftsperson who works at Beverly’s Fabrics, came to sign the treaty and suggested to Devers that the kids create apeace quilt. Devers asked Uchida to spearhead the project.

Now Uchida brings brownies and cookies along with donated fabric and supplies. She teaches sewing and works with some students who say that “nothing” makes them feel peaceful. One girl with a sweet smile and a hoodiedrawn tightly around her head is listening with headphones to music on one of the school’s Mac notebooks while she does her work. Her design is an eagle copied from a book that she colored and Uchida scanned to transfer onto her square.

“The quilt is different [from other projects],” the girl says. “It kept my mind off things. It relaxed me.” When asked if all the kids took it seriously, she answers, “It depends on if the kid has patience. A lot of kids took it more seriously. There are a lot of kids [volunteering to] help after they are done. Everybody has problems, but we need to focus on getting better. I think one day we will have peace.”

She maintains that the school is not filled with a bunch of “bad” kids.

“Our school is just a school with regular kids who have problems and are working on them. We’re not gangs. We’re trying to do better.”

A quiet boy says he enjoys making the designs for the quilt squares for fun, but there will be no impact on ending violence. “It’s not going to change a thing,” he says, so softly it is hard to hear him. “People leave gangs and then come back.”

A tall senior boy has embroidered the State of California with Monterey County outlined in “reggae colors” with a peace sign. He cheerfully says the experience has been really good. “It gives us sewing skills and it makes us more mellow,” he says. “I want to go to college and have a good job working with animals. Mr. Devers is really cool…I feel more confident about myself.”

What started as a small volunteer project for Terry Uchida grew into much more on a personal level.

“I can’t stop thinking about these kids when I’m not with them,” Uchida says, “and I have kids of my own and other responsibilities. I wonder every time there’s a shooting. I wonder was it one of my kids. It has totally changed my outlook on things.”

Shortly after beginning her work with the kids, a tragedy occurred. A 14-year-old boy from class was shot and killed. “He ate my brownies that morning,” Uchida says, still shocked. “He was gone by that afternoon.” Other kids in the class offered to work on the boy’s quilt square. And another girl created a square that says, “RIP My Homie.”

“He’s not a number, he was [the kid I knew],” Uchida says sadly.”He was somebody’s kid, friend, brother. It made it so much more personal.” Uchida says the kids have affected her more than she has helped them.

“They have opened up part of their lives to me,”Uchida says gratefully.”It is so amazing to see these great big tatted, pierced boys finishing three blocks and working on a block for someone who died.These kids are so talented and can be really polite. If I helped one make a connection with one thing in his life, then it’s been worth it.”

When the quilt is completed, Uchida hopes to sell it to raise money for the class or to find a place to display it.

“I don’t know if it will bring peace,” she admits, “I don’t think it is going to change the killings on the East Side. But you’ve got all those boys making tiny little stitches and that’s saying something. Just the fact I have a room full of teenagers [from different sides] sitting and working together, I think that’s peace in whatever form it is.”

The transformations at Salinas Community School have taken place with the help of many other programs, including an outdoor recreation class Devers leads.

“We get kids out of Salinas, outside breathing fresh air, and looking at real things,” he says. “Many have never been to the ocean.We try to take them places they can go back to with their families. They learn to observe, be more in tune with the ecosystem, pay attention to detail. While they are walking together they settle down…We have [people who work with them on] GPS skills, digital photography, sketching and journal writing.”

Devers points out that the kids have had to deal with things that most people couldn’t imagine, and as a result, have “shut down.”Nature, he says, can be the greatest healer. “It used to be a pretty hard- core place and we are turning it into a more loving environment,” Devers says. “A third of the kids are alternative, smart and artsy and don’t fit into [regular] school. They need more attention. A third of the kids are Norteño and a third Sureño.”

Probation officers on campus and strict rules and security enforce that school is a safe place, while Devers tries to keep the emphasis on positive changes. The school, he says, is the only place where kids from rival gangs can co-exist in a safe way. “We have two gangs and all the tension from the streets comes under one roof at one time here, and only here,” Devers says. “School is a place to be neutral and focus on gaining skills and getting a high school diploma. We hope this will result in a different path down on the road.”

For Devers, finding creative projects like the peace quilt is a way to spark a kid’s interest and show that there is more to life than what they’ve seen so far. “The peace quilt is a hugely powerful project and part of a much larger picture of how we are teaching kids,” Devers says. “[We want to] focus on school, personal healing, confidence and self-esteem. We’ve worked hard to make this a nice place.”

For more information on the Peace Quilt project, or starting a project like it, contact Terry Uchida at thatquiltlady@gmail.com. For more information about the Salinas Community School, contact Chris Devers at cdevers@monterey.k12.ca.us. Donations of craft supplies or to the school materials fund are gratefully accepted.