For the past quarter century, Tom Dreesen has been a fixture at the AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am. After 45 years in show business, Dreesen has acquired a lot of famous friends. Sammy Davis, Jr. was one. David Letterman and Clint Eastwood still are. But the man who meant the most to Dreesen, personally and professionally, was Francis Albert Sinatra. For 14 years, Dreesen’s standup comedy was Frank Sinatra’s opening act as they toured the world together. Sinatra was a friend, a confidante, and a tireless booster. Dreesen served as a pallbearer and spoke at Sinatra’s funeral in 1998.

For the past quarter century, Tom Dreesen has been a fixture at the AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am. After 45 years in show business, Dreesen has acquired a lot of famous friends. Sammy Davis, Jr. was one. David Letterman and Clint Eastwood still are. But the man who meant the most to Dreesen, personally and professionally, was Francis Albert Sinatra. For 14 years, Dreesen’s standup comedy was Frank Sinatra’s opening act as they toured the world together. Sinatra was a friend, a confidante, and a tireless booster. Dreesen served as a pallbearer and spoke at Sinatra’s funeral in 1998.

“He meant so much to me,” Dreesen says. “He was like a father to me. He had a profound impact on my life.”

And what a life it’s been: a Horatio Alger story sprinkled with plenty of Tinseltown stardust. Dreesen grew up hand-to-mouth in the Chicago suburb of Harvey, Ill., with eight siblings crowded into a shack with no hot water. He shared a bed with his four brothers, and to help the family scrape by, the young Dreesen set pins in a bowling alley, worked a paper route, and shined shoes at all the local taverns, including the Cedar Lodge Tavern, where his mother was a bartender.

“Growing up, I thought the tavern owner was the richest man in the world,” he says. “That was my dream in life, to own a tavern. I had never been exposed to anything outside of my environment.”

Dreesen’s trajectory was forever altered at age 10, when he began caddying at Ravisloe Country Club, often carrying double 36 holes a day. Instead of rubbing elbows with Teamsters, he was suddenly soaking up the manners and worldview of doctors and lawyers.

“It changed me in a big way,” Dreesen says. “The members didn’t treat me like a slave, they treated me like a son.”

Life in the caddie yard was not so genteel. It was a hardscrabble bunch, and the caddie master kept a pair of boxing gloves around to help settle disputes. Dreesen tops out today at 5’9” and 150 lbs., but then he was a scrawny 105 pounds who nevertheless earned respect as a fearsome scrapper. He boxed for real from 1958-’62, when he served in the Navy and Marine Corps. He also kept playing golf, which he had taught himself at Ravisloe on Mondays, when the club was closed and he could borrow clubs from the bag room. After getting out of the service, Dreesen went to work as an insurance salesman and became active with the Jaycees, helping to spearhead a program to teach the ills of drug abuse by using humor to draw attention while planting seeds of knowledge. As a kid, Dreesen had been entranced watching the Cedar Lodge bartender Frank Polizzi hold court with his customers by telling jokes.

“I was fascinated by how his words could send a charge through the air and suddenly the whole place would explode with laughter,” he says. “I thought he had almost magical powers.”

When visiting elementary schools for the Jaycees, Dreesen picked up a sidekick in Tim Reid, a marketing rep at E.I. du Pont who had just joined the Jaycees. The two had great chemistry together, and one day, an 8th grade girl leaving the classroom said, “You guys are funny; you ought to become a comedy team.”

Dreesen and Reid began working clubs together as a groundbreaking biracial act with edgy material that reflected the roiling cultural shifts of that era. After six years, the team split up. Reid later went on to become “Venus Flytrap” on “WKRP in Cincinnati” and then “Downtown Brown” on “Simon and Simon.” By the early 1970s, Dreesen had made comedy his life’s work. He relocated to Los Angeles and began hanging around the legendary Comedy Store on Sunset Boulevard. The place was haunted by talents that would go on to great fame: among them, Letterman, Jay Leno, Robin Williams and Michael Keaton.

“And Debra Winger was waiting tables!” Dreesen says. He had painstakingly mastered his craft, but Dreesen was still awaiting his big break. “In the eyes of America, if you hadn’t been on Johnny Carson, you weren’t a real comedian,” he says. In 1975, he finally got the nod. “Eight minutes on ‘The Tonight Show’ and my whole life changed,” Dreesen says. He earned a development deal with CBS and became a regular on Merv Griffin’s, Mike Douglas’ and Dinah Shore’s TV shows. Through the years, Carson invited him back five dozen times, and Letterman regularly used him as a guest host. TV and movie work followed. Books and albums would come later. “Comedy was the rock ‘n’ roll of the ’70s,” Dreesen says.

His work with Sammy Davis brought Dreesen into Sinatra’s orbit. They first met at the Golden Nugget in Atlantic City. After the second night’s performance, Sinatra said, “I like your material and I like your style. I’d like you to tour with me.” Dreesen couldn’t help but flashback to his scrappy childhood.

“The first time I heard his voice was when I was a kid working in the tavern back in Harvey,” he says. “It stopped me cold even back then. That voice had never left me.” Sinatra once described their kinship by saying, “We’re a couple of neighborhood kind of guys.”

The gig at the Golden Nugget turned into 50 shows a year, often traveling on Ol’ Blue Eyes’ jet. Dreesen never tired of seeing his name below Sinatra’s on the marquee, and he relished getting to know whom he calls “a very complex man.” For all of his legendary Rat Pack exploits—the parade of famous broads, a bedtime that was never before sunrise—Sinatra had a bedrock set of principles that Dreesen came to adopt: fierce loyalty and unwavering friendship.

“Like all the people around him,” says Dreesen, “I had to learn to never compliment Frank on anything he was wearing, because he would immediately take it off and give it to you, whether it was a pair of cufflinks or a watch worth thousands of dollars.”

In Dreesen’s view, Sinatra had only one serious flaw: “He wasn’t a very good golfer, probably because he was the most impatient person I’ve ever met.” Dreesen, meanwhile, has maintained a single-digit handicap for most of his life. Through Sinatra, he became friendly with Clint Eastwood, which has helped earn him an annual invitation to the Pro-Am.

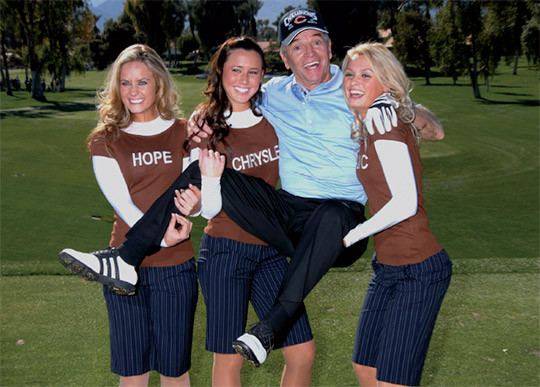

“Every year I’m thrilled they invite me back,” he says. It doesn’t hurt that he always performs at the Wednesday night party for tournament volunteers; just one of the many ways Dreesen gives back. He has been a tireless supporter of the military, doing hundreds of overseas shows for the troops, including two tours of Iraq. For three decades, he has raised money for multiple sclerosis research by running three marathons and hosting a golf tournament to honor his late sister Darlene, who was afflicted by the disease. He has combined his love of golf and philanthropy to host an eponymous celebrity tournament that benefits the Illinois Fatherhood Initiative in his old stomping grounds in Illinois. Dreesen remains deeply connected to his hometown; a few years ago Harvey dedicated the patch of earth where he used to sell newspapers as Dreesen Street.

His annual sojourn to Pebble Beach always puts Dreesen in a reflective mood as to how far

he’s traveled in life.

“Back in the old days, when they’d show Pebble on TV and all the famous people playing

the tournament, it seemed like the most glamorous place in the world,” Dreesen says. “It still does to me. Being a part of the show, it’s just one of my many dreams that came true.”

The 2014 AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am takes place February 3-9. For more information, go to www.attpbgolf.com.