Artists of all types have main-tained a long-held love affair with the Monterey Penin-sula in general, Carmel in particular. For nearly one and a half centuries, all manner—poets, musicians, writers, sculptors, painters—have been drawn as moths to a flame by the area’s unparalleled beauty, temperate climate and (once) inexpensive cost of living. The earliest Bohemian painters formed a tightly woven community of like-minded professionals. The work they produced was distributed throughout the world to people hungry for glimpses of a Wild American West that was swiftly disappearing under the onslaught of rapid population and technological growth. Their legacy lives on in those who followed these pioneers in choosing the Peninsula as the ideal place to work and raise their families.

“Those late 19th- and early 20th-century painters were among the area’s first environmentalists,” says Joaquin Turner, a painter and gallery owner (joaquinturner.com) whose work has been deeply informed and influenced by those innovators. “They saw that the landscape of Monterey was changing,” he says.

The turn of the century was transitional: this stretch of the Central Coast was evolving from the colonial, horse-and-wagon community it was since the 1700s arrival of Spanish explorers. Change came slowly here; it was a sleepy backwater for the most part, but the innovations of the 1900s were slowly being introduced: paved roads were bringing more and more people. The advent of electricity was assaulting the area’s soft candle- and star-lit nights with artificial illumination and its beloved pristine landscape with power lines and poles.

Terry Trotter, owner of Trotter Galleries (trottergalleries.com) with his wife Paula adds, “These artists wanted to capture the feeling of Old Monterey and Carmel. Seeing that the landscape was changing, they consciously wanted to preserve the sense of what it was like for posterity. They knew it would never be the same.”

The stories of these artists are entwined with that of the modern Monterey Peninsula itself. The first art gallery in the state devoted exclusively to California artists was in the luxurious Del Monte Hotel, built by the railroad barons who connected the Golden State with the rest of the nation. Their intent was not altogether altruistic. The wealthy guests who purchased these lovely portrayals of the Monterey area took them home where they were seen by their influential friends who in turn planned trips west, perhaps inspiring them to purchase property on the Peninsula. In short, they were sales tools. But it was a win-win for the artists whose work commanded high prices.

The number of painters that fit this category number in the scores. Here are seven whose work is of the highest caliber and is still highly sought after today. Each was also highly influential to those who followed.

Jules Tavernier

(1844-1889)

Though he lived in Monterey for less than five years, from 1874-79, French-born Tavernier is widely acknowledged as the godfather and founder of the Peninsula art community.

“A classically trained painter, he was already well established in Europe and the US,” explains Terry Trotter. “Tavernier was sent west on assignment from Harper’s Weekly to provide images of the West. By December 1874, he had established his bohemian studio near Alvarado Street in Monterey which quickly became the social hub of a fledgling group of Peninsula artists.”

“Tavernier had an interesting style,” says Turner. “He experimented with different lighting effects, sort of pushed the envelope. He wasn’t afraid to include emotion and drama in his work; it was a departure from the literal depictions popular during the era. This area has so much mood, mystery and romance and he explored and expertly captured that.”

A true Bohemian, the painter—known among peers as “The Knight of the Palette”—counted among his many friends other artists, including writer Robert Louis Stevenson.

Charles Rollo Peters

(1862-1928)

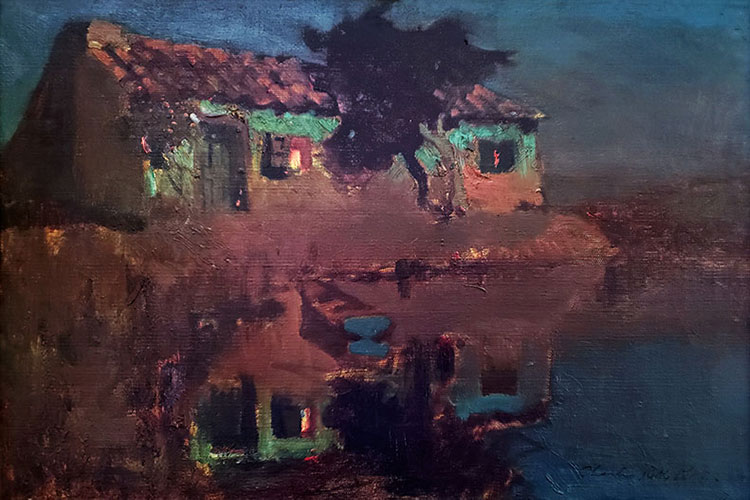

Due to his moody and romantic night-time oils of the crumbling Monterey-area adobes—known as “nocturnes”—Peters earned monikers such as “Poet of the Night” and “The Prince of Darkness.” His social life inspired “The Duke of Monterey” and “Sir Charles.”

In Peters’ day, Monterey was a sparsely populated outpost of melting adobes and sprawling ranchos left over from the Spanish days.

“Peters viewed Monterey as a mystical place and he was a master of capturing that sense of mystery and intrigue,” Turner says. “He didn’t spell everything out, but left room for interpretation. That takes the viewer into his paintings.” He studied under Jules Tavernier for many years.

“One prominent critic of his day said that every good collection should include one of Peters’ exceptional nocturnes,” Terry Trotter says.

Peters was highly commercially successful in his lifetime and by all accounts his money went out as fast as it came in. Peters was famous among his fellow artists for the lavish parties he threw at the home he built on 30 acres southwest of downtown Monterey. That neighborhood is still known as “Peters Gate.”

William Ritschel

(1864-1949)

An LA Times art critic wrote of Ritschel, “Few marine painters know the sea as Ritschel does. You feel in his work the beauty and danger.” Indeed, the Nuremberg-born painter had an abiding love for the ocean, spending several years sailing the world in the German navy. As did Tavernier before him, he enjoyed an international reputation as a painter before coming to California in 1909.

“He was a generous, eccentric character,” Turner says. “He was often seen perched high atop cliffs dressed only in a flowered sarong with brush in hand.”

Ritschel purchased a plot of land in the Carmel Highlands from his friend, developer Frank Devendorf, recognized as “the father of Carmel.” In that dramatic, sea-spray splashed location, he built a home from the granite on which it stood, called “Castel a Mare.”

“Ritschel was not only an active member of the artist colony, but also highly civic-minded,” Trotter says. “During WWI, he donated the many medals he’d won to scrap drives to benefit the war effort.”

Turner had the good fortune to spend a day at the painter’s former residence. “Standing in the backyard you can see where he got the inspiration for many of his paintings. It’s simply stunning.”

Armin Hansen

(1886-1957)

Hansen is also acclaimed for his paintings of the sea, but while William Ritschel concentrated on the ocean itself, this painter is famous for incorporating human activities, such as fishermen, in his compositions.

“Hansen had friends among both avant-garde and traditional painters,” Turner says. “He had one foot in both camps. That’s what I love about his work.”

Trotter adds that Hansen was known as “The Homer of the West” for his visual interpretations of man vs. the sea and “The Rembrandt of the West” for the quality of his etchings.

Ritschel recognized the 32-year-old Hansen’s obvious talent and arranged a show in a New York gallery for him.

“The show opened up a market for the “rough-hewn character from California,” Paula Trotter says. The painter was a big man, 6’4″, 250 pounds, with hands the size of lunchboxes and an outsized personality to match.

“His paintings were as bold as he was. They were described as ‘pure virility,'” Turner adds.

“He was the dean of the local art community for the first half of the 20th century,” Trotter says, “not only for his work, but as a teacher and mentor. He was a natural teacher and was highly regarded among his peers.” As did many of his contemporaries, Hansen felt he owed it to the next generation to pass on his knowledge.

Mary De Neale Morgan

(1868-1948)

Morgan was the Grand Dame of both the cultural and artistic communities of the Monterey Peninsula,” says Paula Trotter. “When she passed away, many leading local artists—including Armin Hansen and William Ritschel—were honorary pallbearers.”

A San Francisco native, Morgan was a frequent Carmel visitor, first pitching a tent in 1903 before moving here permanently in 1910. Unlike many of her contemporaries, she didn’t study outside of California, preferring instead to learn from master painter William Keith of whom she was a favorite pupil.

“She worked in oil, watercolor, tempera,” Turner explains. Morgan was famous for her depictions of the Monterey Peninsula’s sublime Cypress trees, and when asked if she ever tired of painting those haunting trees, she reportedly said, “I will stick by my Cypress trees until they sink into the sea, or what is just as tragic and final, be hopelessly built around.”

A testament to her talent and stature is the fact the first painting sold at the Hotel Del Monte gallery was one of hers.

E. Charlton Fortune

(1885-1969)

Fortune, known as “Effie”, was originally from Sausalito. Born with a cleft palate, she grew up a loner, studying art in Scotland before returning to her home state in 1905. She first made her mark in the art world painting portraits of notables, but after turning to landscapes, all her paintings were tragically destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Once in Monterey, she built a magnificent home that still stands on High Street between Jefferson and Roosevelt where she lived and worked for many years.

“She could paint as well or better than most men of her time,” Terry Trotter says. “She was a painter’s painter.” And as did women of her time, Fortune suffered discrimination. “Effie Fortune signed her first name with only an initial, so as not to emphasize her gender. This was helpful toward acceptance into predominately male juried exhibitions, thus also increasing chances for awards.”

Fortune was a key player in and revered member of the Peninsula art colonies until her passing in 1969.

Jo Mora

(1876-1947)

Mora was an extremely colorful character, a Renaissance man who excelled at everything he undertook—and he undertook a lot: he was a horseman, linguist, illustrator, photographer, watercolorist, writer, map maker, sculptor, painter, muralist, cartoonist, actor.

“His mastery of such varied mediums and sheer volume of work is truly amazing,” says Turner.

“He also had a true sense of humor rendered in much of his work,” Terry Trotter says, “and many of the Mora items on display in the Pacific Grove Museum/Gallery are prime examples.”

Mora once rode on horseback from Baja California to San Jose, stopping along the way to work on ranches to earn enough to keep moving. “Mora also lived with the Hopi and Navajo tribes for two years, learned their languages and painted and photographed their villages and relics,” says Turner.

Mora’s work is seen all over the Peninsula, most remarkably at the Carmel Mission where he created the cenotaph of Father Junipero Serra. “He considered this sculptural commission above all others to be the most important of his career,” explains Paula Trotter.