Most people think of the giant kelp seen along Monterey Bay’s shoreline as “seaweed,” but the truth is, it’s not a weed—it’s not even a plant, but a form of algae. Scientists refer to it fondly as Macrocystis pyrifera and it is one of the planet’s fastest-growing species, shooting up two feet a day in optimal circumstances, sometimes reaching lengths of 175 feet. Kelp is found in the temperate waters of the Southern Hemisphere and along the eastern shores of the Pacific. One would think that with that phenomenal rate of progress it wouldn’t be long before kelp overwhelms the bay—and the wider ocean, for that matter.

But Mother Nature had other plans. Around 2014, California coastal water temperatures began trending upward—alarmingly. Known as “The Blob,” an area of warm water began growing in the Pacific Ocean. This water was low in nutrients, stressing the kelp, and The Blob stayed around for several years. Its existence coincided with a disease that devastated the sea star population, including the sunflower sea star, a critter whose favorite food is the purple sea urchin. Consequently, with its main predator out of the picture, the urchin population skyrocketed. And what do urchins eat? Kelp. You might see where this is going.

A kelp forest is a diverse, dynamic, complicated ecosystem. It fastens itself on the seabed with a mechanism known as a “hold fast” and maintains positive buoyancy with air-filled pots that lift the organism toward the sun. All the nutrients needed for survival and growth are obtained from the surrounding water—sort of like an aquatic air fern. Even though not a plant, kelp uses the sun’s energy through photosynthesis and thereby is one of the Earth atmosphere’s most efficient scrubbers of carbon dioxide. They support many, many species of sea life, including rockfish, jellies, crabs, snails and shrimp. Mammals like them too. Otters are often seen lying on a bed of kelp in the surging waters and seals and sea lions hunt among the fronds. Even birds get in on the action.

Keith Rootsaert is founder and executive director of the Giant Giant Kelp Restoration Project. “Giant kelp is the foundation for so much life in the ocean,” he says. “Hundreds of species depend on it.” Grad students at UC Santa Cruz studied historical satellite photos of the Sonoma and Mendocino coasts and determined that full 95% of the kelp forest had

vanished over three to four years. Rootsaert says the situation in Monterey Bay is comparable. “We’ve had an 88% kelp loss. What was

487 acres of kelp forest prior to the marine heat wave is now down to 58.3.” Of that number, 11 acres are due to the Project’s efforts.

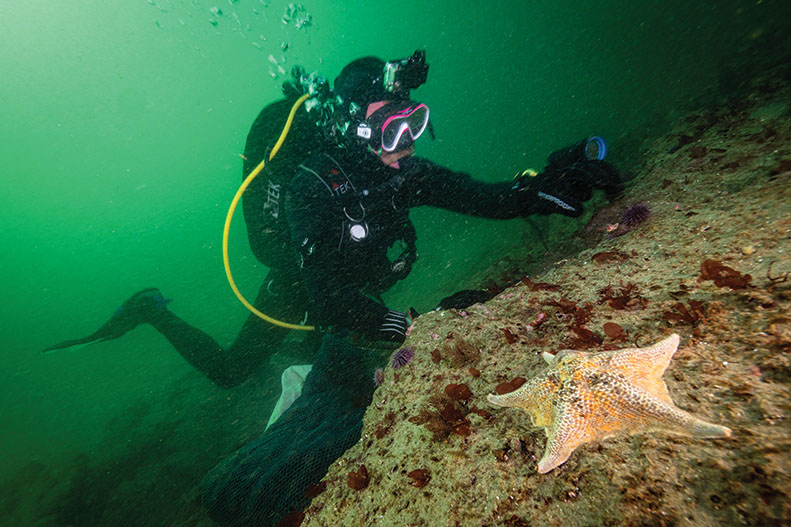

Gregarious and energetic, Rootsaert is extremely passionate about the project. He learned to dive in Monterey Peninsula waters in the 1980s and returned to recreational scuba in 2009 after a hiatus. “I was amazed in the ’80s by how beautiful the kelp forests were and how life filled every available spot on the seabed,” he says. “That was my baseline for what a healthy kelp ecosystem looked like. When I resumed diving, I realized that I wasn’t seeing as many fish as I did in the ’80s.” Then that heat wave hit. “We saw urchins change their behavior. They started eating more and more kelp.” In April 2021, he recruited divers to manually remove urchins from the biota. They set up a two-and-one-half-acre grid on a section of seafloor off Sand City known as Tanker’s Reef (so called because oil tankers anchored there while awaiting the loading of crude oil piped in from Coalinga via what is now Monterey’s Wharf #2) and started harvesting the spiny animals. To qualify for participation, divers must possess an Open Water Level Certification, have at least 20 cold-water dives under their weight belts and pass a kelp restoration specialty course through certification agencies PADI or NAUI. This course is administered through local dive businesses such as Aquarius Dive Shop.

Many times, the dives are done at night, because the urchins tend to hide during daylight. “Since the program’s inception, 214 volunteer divers have collectively made nearly 1,377 dives for a total of 1,014 hours underwater. To date, harvesting 637,000 urchins from the reef.” The goal is to clear 2,000 acres by 2030, allowing the kelp to flourish once again. “This is not a temporary problem,” Rootsaert says. “We have to keep going back.”

For more information or to get involved, visit www.g2kr.com or call 408/206-0721.