Sitting outside her Carmel home on a winter afternoon, sipping tea by the fire, award-winning author Meg Waite Clayton put her pen down and took a moment to talk about her latest book, “The Postmistress of Paris,” and the process of pursing a story.

This book is a work of fiction. And yet, in many ways, it’s all true, or so it seems—the result of

historical fiction, relentlessly re-searched and written throughout France. Both the story line and the author’s investment in it offer tales of passionate pursuit, which is what makes Meg Waite Clayton a New York Times bestselling author. That, and the kind of crafting that shifts her audience from readers to witnesses, there in the moment, experiencing the story, themselves.

It is the descriptive detail woven throughout “The Postmistress of Paris” that makes each moment tangible. It is knowing history well enough to give her story a sense of accuracy. It is understanding her characters so clearly, it’s as if she knows them. There’s also a reason Clayton dedicates the book to her mother, Anna Tyler Waite. She, too, is in the details.

We don’t learn the protagonist’s name until partway through page seven. And even then, only her first name, Nanée. Yet we’ve already become quite acquainted with her.

The story emerges in Paris, early 1938, and spans just two years, but it is burdened by history. “The Postmistress of Paris” has nothing to do with delivering mail. Nanée is providing something more important: the information that might enable those in hiding—during the German occupation of Paris—to survive.

Clayton dedicated the book to her mother because Nanée is strong-willed, gutsy, in a way she believes her mom was. She overcame obstacles, persisted, paved her own path. “She wasn’t born an heiress but built her own kind of fortune,” says Clayton, “in her own way. It took real dedication.”

Her mother’s birthday was November 8th. The book publication date was November 9th. Due to her mother’s illness, Clayton didn’t imagine she’d make either event. Despite a two-week delay in publication, Anna Tyler Waite lived another 18 months and was present for the book release.

“My mother loved that I wrote, and she believed I could do it. A book was done,” says Clayton, “when she said it was. I loved talking about writing with her. I later found some of her own writing on her computer.”

Becoming Meg Waite Clayton

She had known she wanted to be a writer since she was a child. Yet it took Clayton a long time to give herself permission to pursue it.

“Knowing you want to write, and believing you can are two different things. I’ve always been a huge reader. I think my desire to write was less about writing to tell stories,” she says, “and more about what novels did for me, creating a kind of magic. But I was a math-and-science girl. My weakness was English.”

In fact, English was the only non-Advanced Placement class she ever took in high school. She got through it by taking a Tolkien class, pass-fail.

“I admit and can embrace that I’m Type A. I like to be right and to know I am. In math,” she says, “you do. In English, you can’t be sure. As a writer, I see all those things that are not concrete; the bird on the wire can mean so many things to so many people.”

So, Clayton became a corporate attorney in a big law firm, working hundred-hour weeks, and finding a concrete kind of success. It was her husband, Mac Clayton, having already culminated his own law career, who gave her permission to reconsider her career path.

“Mac poured me a glass of wine and asked if there was anything else I’d like to do, if I were to set aside what I knew I could do to explore something else. I said I’d like to be a novelist. His confidence in me, his belief I could do it,” she says, “gave me permission to try, even if I failed.”

Not trying, he told her, was the only real definition of failure.

Clayton left law at age 32. She was up for partner at her firm, and when it didn’t happen, it felt like the push she needed, another sign of permission. Besides, she was pregnant with her second child. It was time for a change.

“For me, being a novelist meant being able to leap tall literary buildings in a single bound,” she wrote. “So I had gone off to the University of Michigan, thinking I would become a doctor and emerged as a corporate lawyer in a tidy blue suit. It took time to work up the nerve to give writing a serious try.”

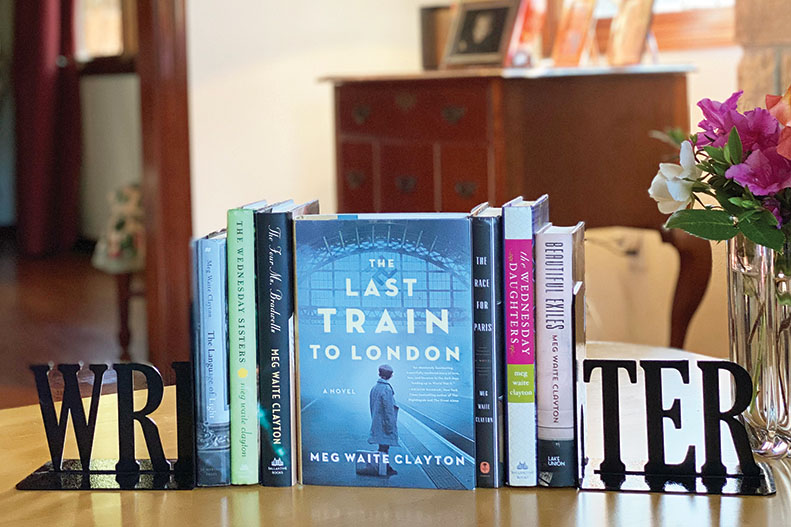

Her second son was 11 when she published her first novel, in 2003. A story of starting over by fleeing the family home as a way to escape grief and rediscover one’s self, “The Language of Light: A Novel,” was a finalist for the PEN/Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction. The award, granted to a United States citizen for a previously unpublished work of fiction that addresses social justice, was established by legendary author Barbara Kingsolver. “The Postmistress of Paris” is Clayton’s eighth novel.

“Writing,” says Clayton, “is a lot harder than it looks.”

For more information about Meg Waite Clayton, visit www.megwaiteclayton.com.